- Home

- Liz Braswell

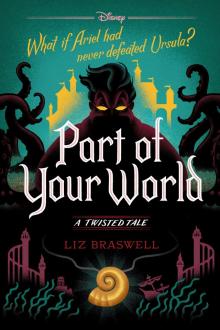

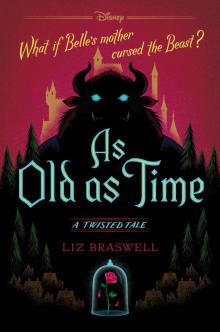

As Old As Time: A Twisted Tale (Twisted Tale, A)

As Old As Time: A Twisted Tale (Twisted Tale, A) Read online

Copyright © 2016 Disney Enterprises, Inc.

Cover design by Scott Piehl

Cover illustration by Jim Tierney

All rights reserved. Published by Disney Press, an imprint of Disney Book Group. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information address Disney Press, 1101 Flower Street, Glendale, California 91201.

“Mirror” from Crossing the Water. Copyright © 1963 by Ted Hughes.

Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

“Mirror” from Collected Poems by Sylvia Plath.

Reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

ISBN 978-1-4847-0749-4

Visit disneybooks.com

Contents

Dedication

Mirror

Part I

Once Upon a Time

Before the Beginning

The Girl Is Strange—No Question

Happily Ever After

Always the Bridesmaid

A Kingdom Sours

An Enchanted Castle

The End of Fairy Tales

The Enchanted Castle

The Christening

Be Our…Oh, You Know the Rest!

Flight

The Extremely Fascinating Tour of a Historically and Architecturally Important Landmark Castle

Death and a Curse

The Rose

Endgame

Curiosity Killed the Beast

What Belle Saw

A Curse Descends

Part II

Escape

A Decision and Its Consequences

A Castle, Haunted

The Library

And Her Nose Stuck in a Book

Mrs. Potts Loses Her Tea

La Cuisine de la Maison

Dinner Is Served

Ask the Dishes

Meanwhile, Not at the Castle…

She Didn’t See It There Before

Gaston

An Old Crime

To Sleep

Kidnapping

A Lead

Reunion

Part III

The Play’s the Thing

The Beast

Papa

The Beast’s Nightmare

Belle’s Nightmare

There’s Something Truly Terrible Inside

Overheard

This Same Old Town

Escape

Reunion

A Tale (as Old as Time)

All Together

Endings

About the Author

For my husband, Scott. Without your support, love, and presence these books—and certain days ending in y—would be a whole lot harder.

And a gigantic, fluffy THANK YOU to my editor, Brittany, whose sense of fun and brilliant ideas made over a thousand pages seem to just fly by

—L.B.

MIRROR

I am silver and exact. I have no preconceptions.

Whatever I see I swallow immediately,

Just as it is, unmisted by love or dislike.

I am not cruel, only truthful‚

The eye of a little god, four-cornered.

Most of the time I meditate on the opposite wall.

It is pink, with speckles. I have looked at it so long

I think it is part of my heart. But it flickers.

Faces and darkness separate us over and over.

Now I am a lake. A woman bends over me,

Searching my reaches for what she really is.

Then she turns to those liars, the candles or the moon.

I see her back, and reflect it faithfully.

She rewards me with tears and an agitation of hands.

I am important to her. She comes and goes.

Each morning it is her face that replaces the darkness.

In me she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman

Rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish.

—Sylvia Plath

Once upon a time in a faraway land, a young prince lived in a shining castle. Although he had everything his heart desired, the Prince was spoiled, selfish, and unkind.

But then, one winter’s night, an old beggar woman came to the castle and offered him a single blood-red rose in return for shelter from the bitter cold. Repulsed by her haggard appearance, the Prince sneered at the gift and turned the old woman away—although she warned him not to be deceived by appearances, for true beauty is found within. And when he dismissed her again, the old woman’s ugliness melted away to reveal a beautiful enchantress.

The Prince tried to apologize but it was too late, for she had seen that there was no love in his heart. As punishment she transformed him into a hideous beast and placed a powerful spell on the castle and all who lived there.

“You have until the eve of your twenty-first birthday to become as beautiful on the inside as you were on the outside. If you do not learn to love another—and be loved in return—by the time the last petal of this rose falls, you, your castle, and all within, will be cursed and forgotten forever.”

Ashamed of his monstrous form, the Beast concealed himself inside his castle, with a magic mirror as his only window to the outside world.

As the years passed, he fell into despair and lost all hope—for who could ever learn to love a beast?

It was a very good story.

It often entertained the woman who lay in her black hole of a room, manacled to a hard, cold bed.

She had enjoyed its repetition in her mind for years. Sometimes she remembered bits differently: sometimes the rose was as pink as a sunrise by the sea. But that never resonated as well as red as blood.

And the part at the very end, where the Enchantress is waylaid upon exiting the castle, thrown into a black carriage, and spirited into the night—well, it didn’t sound as epic and grand. She never included it.

Almost anyone else would have run out of thoughts by this point. Almost anyone else would have given in to the finality of the oubliette until she forgot herself entirely.

A few of her thoughts were crazy, spinning around and around the dried teakettle that was now the inside of her head. If she wasn’t careful, they would become too speedy, break free, and seek escape through the cracks of her mind. But that way lay madness, and she wasn’t quite there yet.

Ten years and she had almost forgotten herself. But not quite.

Footsteps down the hall.

She shut her eyes as tight as possible against the madness from without that tried to intrude upon her black personal madness.

Chattering voices. Another set of footsteps. The swish swish of a rank mop against the endlessly slimy floors. The clink of keys.

“No need to do that one. It’s empty.”

“But it’s locked. Why would it be locked if it’s empty?”

She had to scream, she had to shake, she had to explode—anything rather than let the dialogue repeat itself yet again as it had for the last four thousand days, in only slightly different iterations:

“Ooh, this one’s locked. But do you hear something inside?”

“This door’s closed. You think it’s locked?”

“The one down here is locked—but I don’t remember anyone being put down here.”

It was as if God were trying out all the different possible lines in the mummer’s farce that was her life and still hadn’t gotten it quite right.

The next two minutes were as predictable as the words from a parent to a child who kn

ows she has misbehaved and chafes under the inevitability of the sentences hurled at her.

Turn of the key in the lock.

Door creaking open.

A hideous face, hideous only in its familiarity, the same look of surprise as always and every day since forever began. The face’s owner carried a tray with her in the hand that didn’t have the keys. Behind her, in the hall, stood the woman with the mop. And behind her stood a large and silent man who was ready to subdue any of the prisoners not tied down.

The prisoner found herself opening her eyes, curiosity getting the better of her survival instinct. Today’s tray had four bowls of broth. Sometimes it was five, sometimes it was three. Sometimes there was only one.

“Lucky for you I got an extra,” the one with the tray said, settling herself down in a filthy tuffet of skirts and aprons.

This line never changed. Ever.

The prisoner screamed, unable to contain herself, unable to keep herself from looking forward to that one thing each day—the thin gruel that passed for nourishment.

The woman with the mop muttered indignantly.

“I didn’t hear nuffink about a new one, I can tell you that. Thought they done a right good job clearing these sorts out of the world.”

“Well, there’s one now. There you go, finish up now.”

The woman said it with the same false tenderness she expressed every time. The bowl tipped faster, broth trickled down the sides of the prisoner’s neck and, despite herself, she got desperate, straining against the chains and sticking her tongue out to get every last drop before the bowl was removed.

“This one is old enough to be a mother,” the gruel woman said without a trace of emotion or sentiment. “Think of that, them having children and raising them and all.”

“Like animals, all of them. Animals raise their children, too. I don’t know why they keep them around. Kill ’em and be done with it.”

“Oh, soon enough, soon enough, no doubt,” the broth hag said philosophically, getting up. “They don’t last long around here.”

Except, of course, it had been ten years now.

This time the hag didn’t bother to toss some platitude over her shoulder as she left; the prisoner’s existence was forgotten the moment she touched the door and was on her way out.

It would be all new again for her and her horrible companion tomorrow…and the next day…and the day after that….

The prisoner screamed one last time, finally and uncontrollably, as the darkness closed in.

She had to start the story again. If she just started the story and played it through, everything would be all right.

Once upon a time in a faraway land, a young prince lived in a shining castle…

Once upon a time, slightly longer ago than before, there was a kingdom whose name and very existence have long since been forgotten. While the rest of the world was fighting for control of new lands across the seas, inventing ever more deadly weapons, and generously gifting their own religion to foreign people who didn’t want it, this kingdom just splendidly was.

It had fertile croplands, dense hunting forests, a neat little hamlet, and the prettiest postcard castle anyone had ever seen.

In happier years, because of its removed location in an out-of-the way valley, it was a lodestone for the artistic, the different, the clever: les charmantes. They fled there as the modern world closed in on the rest of Europe. The little kingdom passed the Dark Ages and the Renaissance peacefully and uneventfully. Only now were the diseases of civilized man finally catching up.

Even so, here there were still fortune-tellers who could actually tell your fortune, farmers who could pull water from stone during a dry season, and performers who could really turn boys into doves. And sometimes back.

The kingdom also drew those who didn’t have powers, precisely, but their own unusual natural talents and quirks—those who felt comfortable among the other folk. Misfits and dreamers. Poets and musicians. Nice oddballs, finding refuge there in a world that didn’t want them.

One was a young man named Maurice. The son of a tinker, he had both the will to wander and the skill to fix and invent. Unlike his father, however, he felt a change in the ancient air of Europe. Wonderful, mechanical change: a future filled with weaving mills powered by steam, balloons that could carry people to far-off lands, and stoves that could cook meals all by themselves.

Determined to be part of all this, Maurice looked to both the past—the steam engines of Hero—and the present, desperately chatting up anyone who had a firsthand account of the marvels he had read about. His longing took him all over, chasing down gears and pistons and demonstrations of science.

But he realized that a life of wandering would get him nowhere; he needed someplace he could sit and think for a while and tinker with really big things—machines that required huge fires and mighty smelters. Someplace he could store all his junk.

In short, he needed a home.

Following his heart and rumors, he wound up in a corner of Europe that was just a bit out of sync with the rest of the world.

First he stopped at a tiny village on a river that was perfect for powering waterwheels. But after observing the provincial little lives of the people there and enduring their horrified looks at his handcart filled with goggles and equipment and books, he realized that it was not the right place for him.

He crossed the river and went on through the woods, winding up in the strange kingdom where it wasn’t unusual for someone to be seen whispering to a black cat—and the cat whispering back—or having a drink at the local pub, still covered in silver soot from the day’s work and wearing dark mica goggles. Where he would fit in.

Maurice immediately struck up a friendship with some local lads and ended up renting a place with one of them. Alaric, more into animals than machines, managed to get them a cheap room at the back of one of the stables where he hired himself out as a groomsman.

While the lodging itself was tiny and reeked of horses, it did include access to a large common yard. Maurice immediately set about constructing a forge, kiln, and tinkering table.

He happily betook any hard labor that would bring him closer to getting the right bits for his latest project. While he picked rocks out of fields or hauled sheaves of grain on his shoulders, his mind was far away, thinking about the tensile strength of different metals, the possibilities of alloys, and how to achieve the perfectly cylindrical, smooth shape he needed for the next step.

“Old Maurice Head-in-the-Clouds,” his fellow strong lads would say, clapping him on the shoulders. But it was always said with a smile and respect, the same way they called Josepha the tavern maid “the Black Witch.” Her punch was strong—and the shocks she could deliver with a snap of her fingers to irksome customers even stronger.

At the end of summer, all of the able-bodied young men were working in the fields—even Alaric, who preferred horses to the oats they ate. Sunburned and with aching backs, they staggered into town every evening, throats parched but still singing. And, of course, they made their way directly to Josepha’s.

One night, while his friends piled into the tavern, Maurice hung back to dust himself off as best he could—and to get a better look at a bit of a commotion occurring just outside.

A giant and solid-looking man stood with his legs spread aggressively and a dangerous look in his eye. This was interesting, but not as intriguing as what else was going on.

Sticking her face into the man’s was one of the most beautiful women Maurice had ever seen. She had the poise of a dancer and the body of a goddess. Her hair glowed golden in the sunset. But bright red spots of rage flushed her beautiful cheeks, and her eyes flashed green with indignation.

She waved a slim alder wand in the air for emphasis:

“Nothing is unnatural about us!” Her words were perfectly formed and accented; it was emotion that caused her to nearly spit. “Anything God makes is natural—by definition. And we, all of us, are the children of God!”

“You are the children of the devil,” the man said calmly, lazily. Like someone who knew he was going to win. “Put here as a test. You shall be wiped from the earth like the unnatural dragons of old, you mouthy hag. Unless you purify yourself.”

“Purify?” The girl actually spat this time. “I was baptized by the monsignor himself—so that is at least one more bath than you’ve ever had, you son of a pig!”

The man made a movement, a very slight one, reaching to his waist. As good-natured as Maurice was, he had traveled enough to know what that signaled: a knife, a pistol, a backhand across the face. Something violent. He acted immediately, moving to run over and help her.

But it was all over before he took a single step: there was a flash brighter than lightning, completely silent. Everything went stark white.

After a few moments, Maurice could see again. The girl was storming off angrily but the man still stood there. There was indeed a pistol in his hand that he had meant to use. It fell to his side, now forgotten. More pressing business occupied the man’s attention. Where his nose had been, there was a now a bright pink snout.

“Son of a pig…” Maurice repeated slowly, beginning to smile. “Pig!”

He chuckled to himself and finally went into the tavern.

He found Alaric with the usual gang, along with someone new: a thin, drawn-looking young man who folded his body over and brought his shoulders together like an insect, a very unhappy one. His clothes were dark and the expression on his face nervous and dour—in every way the exact opposite of the fair-haired and sunny groomsman.

Maurice moved toward them slowly, still thinking about the incident outside. Not the flash or the fight or the pig’s nose, but the way the setting sun had gleamed on the girl’s tresses.

Alaric impatiently pulled him down into a seat between himself and the brooding fellow.

“Here, sit already! Have you met the doc yet? I don’t think you have. Frédéric, Maurice. Maurice, Frédéric.”

Maurice nodded absently. He hoped he wasn’t being rude. Without being asked, Josepha placed a tankard of cidre down in front of him.

“Pleased to meet you,” Frédéric said crisply, if gloomily. “But I am not a doctor, I keep telling you that. I was meant to be one, once…”

Unbirthday

Unbirthday Straight On Till Morning

Straight On Till Morning A Whole New World

A Whole New World Once Upon a Dream

Once Upon a Dream Part of Your World

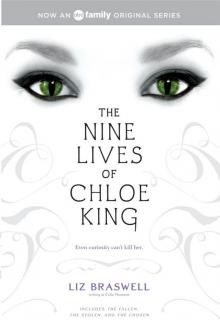

Part of Your World Nine Lives of Chloe King

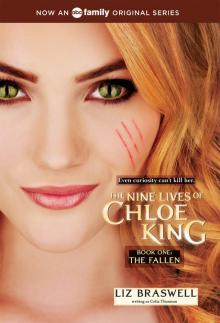

Nine Lives of Chloe King The Fallen

The Fallen As Old As Time: A Twisted Tale (Twisted Tale, A)

As Old As Time: A Twisted Tale (Twisted Tale, A)